I’m reviewing the today (sponsored review — they sent me the Bible I’m reviewing) over at Titus 2 Homemaker. It’s a lengthy review with lots of detail, so if you’re at all interested in this Bible, go check it out!

tools and resource recommendations to help you get the most out of your Bible study

I’m reviewing the today (sponsored review — they sent me the Bible I’m reviewing) over at Titus 2 Homemaker. It’s a lengthy review with lots of detail, so if you’re at all interested in this Bible, go check it out!

If you’re new to the Bible — and maybe even if you’re not — you may be wondering what the italicized words are in your Bible.

Unlike in most other contexts, the italicized words are not for emphasis. In fact, it’s almost a kind of de-emphasis. The italicized words have been added by the translators, for clarity or to improve sentence flow in English, but aren’t in the original text (where word order, grammar, etc. are often different due to language differences).

In most cases this is pretty insignificant. Minor words are added to prevent sentences from being clunky, like this:

because what may be known of God is manifest in them, for God has shown it to them. (Romans 1:19)

Sometimes it’s making the grammar more obvious or making clear where the repetition of a word is implied by actually repeating the word. As in these examples:

Paul, a bondservant of Jesus Christ, called to be an apostle, separated to the gospel of God which He promised before through His prophets in the Holy Scriptures, concerning His Son Jesus Christ our Lord, who was born of the seed of David according to the flesh, and declared to be the Son of God with power according to the Spirit of holiness, by the resurrection from the dead. (Romans 1:1-4)

Imitate me, just as I also imitate Christ. (1 Corinthians 11:1)

But it’s worth paying attention to when you’re studying a passage, because occasionally there’s some interpretation involved in adding these words, and it can change the overall emphasis of the sentence.

For this reason the woman ought to have a symbol of authority on her head, because of the angels. (1 Corinthians 11:10)

If you’re just reading, I wouldn’t worry too much about this. But if you’re sitting down to study a passage, I encourage you to mentally read through the verse without the added words. Does the (potential) meaning of the sentence change or just the sentence just get clunkier? If it’s just clunky, then you can assume the words are solely impacting the flow. But if they change the meaning of the sentence, it might be worth reconsidering whether the words should have been added, or if that was presumptuous on the part of the translators.

Many thanks to Lifeway Christian Resources for providing a sample of the product for this review. Opinions are 100% my own and NOT influenced by monetary compensation. Please note that this review is being simultaneously published on my other blog, which is why the watermarks on the pictures look like they come from somewhere else. I didn’t steal them; I promise!

I have to confess I wasn’t sure what to expect when I heard about The Old Testament Handbook from Lifeway/Broadman & Holman. Lifeway is associated with the Southern Baptist Convention, and there’s been a bit of upheaval in the Convention the last few years, so I didn’t know where to expect this to land, theologically. So far, I have not been disappointed.

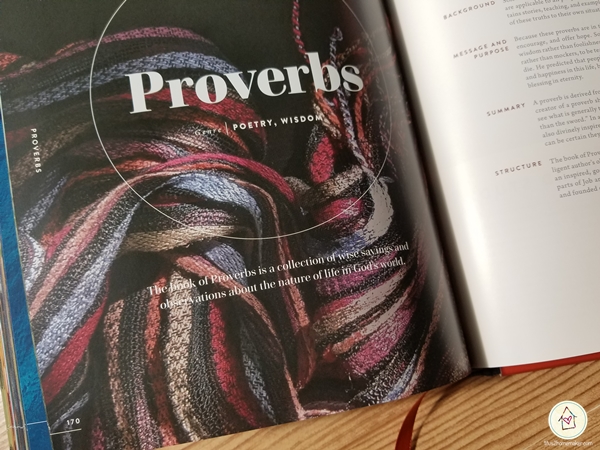

First of all, this book is simply beautiful. The outside is pretty simple and unassuming — just a plain grey cover with embossed title. But it’s quality. That grey is cloth, and it covers a hardbound, sewn binding so this book will last for a long time.

The interior is full-color, glossy, and (I know I’m repeating myself) just beautiful. Each book of the Bible has its own aesthetic theme, with a photo featured on the title page and along the outer edges of the page. (This also serves to differentiate the sections as you flip through.)

There really isn’t much by way of front matter. If I had any complaints about the book, this would be it. It lists the books (and an introductory section about the Bible in general, and “sources” at the end), but there’s no list of the resources within each section. You just have to flip to them to see. For the most part, this is not a big deal, but it would have been nice to be able to quickly identify the page number for a resource you already know is there – or to cross-reference in instances where the content is relevant to more than one location in Scripture.

For the most part, there’s one section per book. In a few instances, books are combined: 1 & 2 Kings are a section — the same with 1 & 2 Samuel and 1 & 2 Chronicles. Ezra and Nehemiah are paired, and all of the minor prophets are a single section. Each of the other books is a standalone.

For the most part, there’s one section per book. In a few instances, books are combined: 1 & 2 Kings are a section — the same with 1 & 2 Samuel and 1 & 2 Chronicles. Ezra and Nehemiah are paired, and all of the minor prophets are a single section. Each of the other books is a standalone.

Within each section, there are some constants.

Each section begins with an introduction that tells about the author, background, message and purpose, and structure of the book, and also provides a summary. This is followed by an outline, and a word study of 1-4 (usually 3) Hebrew words that are significant in that book.

The rest of the contents vary. Many of the books include a timeline.

Others contain maps.

Many contain various comparative charts that help provide a quick overview of information within a book, or to compare its content with other Old Testament books or demonstrate how it points to the New Testament and Jesus.

It’s hard to be any more specific than that without just listing everything. The maps, charts, etc. depend on what makes sense for the content of each individual book, so they vary considerably. We have everything from Abraham’s family tree to a diagram of the tabernacle to giants in the Bible to “seeing Jesus in the divided kingdom.”

Sprinkled throughout are full-page “key verses” (Scripture) and “key quotes” (theologians’ words).

As you may have noticed if you were paying close attention to the photos, the Bible translation used throughout this book is the Christian Standard Bible.

Given how pleased I was with the overall content of The Old Testament Handbook, I was also excited to see this slipped over the back:

The publisher is giving one of you readers a $10 Amazon gift card. (You can use it toward your own copy of The Old Testament Handbook. 😉 )

The giveaway is now over. Congratulations to Amy F.!

#OldTestamentHandbookMIN #theoldtestamenthandbook #christianstandardbible #CSB #holmanhandbookseries #holmanhandbook #holmanbibles #othandbook @christianstandardbible @bhpub

Which is the best version of the Bible? That’s a seemingly simple question with a not-so-simple answer. There’s one very simple principle involved in choosing which Bible to read, but putting it into practice requires a little bit of background. So let’s talk about how to choose a translation.

The most fundamental bit of background is that the Bible wasn’t originally written in English. Most of the Old Testament was written in Hebrew and most of the New Testament was written in Greek, with a little bit of Aramaic in places. That means anything we read in English has been translated — which means all the normal difficulties of conveying ideas from one language in another language come into play. And that brings us to the one simple principle:

The best version of the Bible is the one that best balances readability in English* with accuracy in conveying the ideas originally written in Hebrew, Greek, or Aramaic.

*I’m assuming you’re an English reader since this site is written in English. If your native tongue is something else, then the same is true for whatever language you normally read in.

There isn’t necessarily a single best version; there are a handful of good ones.

There are two basic approaches to translation: formal equivalency and dynamic equivalency, which can be explained as “word for word” and ” thought for thought,” respectively. Various translations exist along a spectrum, with some being more formal and others being more dynamic.

No translation uses perfect formal equivalency — at least not the kind designed for normal reading. (Certain interlinear Bibles made for pastoral study can be.) Not only are things like word order different from one language to another; certain phrases simply aren’t meant to translate that way.

Imagine, for instance, if someone translated “it cost an arm and a leg” literally into a language where that idiom is not used! It would probably be both less confusing and more accurate to translate this as something like “it was very expensive.”

Dynamic equivalencies, then, tend to make a text more reader-friendly. In exchange, though, you lose some precision of language, which can trip you up when you’re studying if the translation leans too heavily that direction.

If you go too far down the scale into dynamic equivalency, you start to get into versions that are really paraphrases, not translations, because they’ve diverged so far from the original — often inserting new idioms, etc. Consider, for instance, Galatians 5:26 in three different versions:

Let us not become conceited, provoking one another, envying one another. (NKJV)

Let us not become conceited, provoking and envying each other. (NIV)

That means we will not compare ourselves with each other as if one of us were better and another worse. We have far more interesting things to do with our lives. Each of us is an original. (The Message)

NKJV is primarily a formal equivalency translation; NIV is a dynamic equivalency translation; The Message is a paraphrase. As you can see, the content of the NIV is essentially the same as that of the NKJV, but you’ve lost the parallel sentence structure. For reading, that’s no big deal; for studying, there might be something to be gained from seeing parallels like this.

But The Message is…not very close. It’s two or three times as long and, although you can find the “conceit” and “envying” idea in there if you look closely enough, the idea of “provoking” one another is missing, and “each of us is an original” is entirely added.

I don’t recommend paraphrases at all, except perhaps as supplemental reading for someone who’s already very familiar with the text in a more accurate translation. It’s just too hard to separate what God originally said from ideas imported by the paraphraser, which can be spiritually dangerous.

The New International Version (NIV) and the New Living Translation (NLT) are about as dynamic-leaning as you can get before, in my estimation, you’re not really dealing with translations anymore. Some people might prefer these for everyday Bible reading. (The NLT is right on the line between a translation and a paraphrase. It would probably be my last choice, even for reading — something I’d only recommend for someone whose reading skills don’t allow for comprehending anything more literal.)

For study, you’ll likely want something more literal — a pretty heavily formal equivalency-leaning version. A few good ones include:

The publishers of the Christian Standard Bible (CSB — the recent Southern Baptist-originating translation) say that it’s about midway between those four and the NIV.

So my recommendation would be to use NKJV, MKJV, ESV, or NASB for study and, if you’re more comfortable with something more dynamic for everyday reading, the CSB or maybe NIV — or the NLT for poor readers. Essentially, I’d aim for the most literal translation your reading skills will allow you to read with reasonable comprehension.

There’s a reason we have newer translations like the NKJV and MKJV — the original King James Version is dated. It’s a solid translation…for its day. But many of the words no longer mean the same thing today, which has the potential for causing confusion or, worse, causing the reader to think he understands what he just read when, in fact, the words mean something different to the 17th-century reader.

For example, you know what “prevent” means, right? It means to keep something from happening; to hinder. Look it up here, though. Go ahead; I’ll wait.

Pretty different, right?

What about “incontinent”? The primary — virtually only — usage of this word today wasn’t always the primary usage. You’ll be relieved (no pun intended) to know that Paul was not telling Timothy that the last days would bring mass lack of bladder control.

By now I’m sure you get the idea. The KJV is sound as a translation, and if your church or family already uses it, I wouldn’t necessarily suggest you abandon it. But if you’re looking for a translation, it isn’t among my top picks.

If you’d like to dive into this (and other translation factors) deeply — but without getting too academic — there’s a great series which is, unfortunately, defunct online but which is available through The Internet Archive. Propadeutic’s Comparing Bible Translations offers a list of suggested questions to ask about a given translation and then provides some analysis of some of the major translations for each one. (Note that this is too old to include the CSB.)

If you’re a total newbie to the Bible, this analysis is likely to be like drinking from a fire hose (unless you just happen to personally enjoy that type of analysis), so if that’s you, you might want to just stick with my simpler explanation & assessment here.

If you’ve never read the Bible before, it can be pretty overwhelming. It’s long, it’s unfamiliar, and you didn’t have a high school or college course called How to Read the Bible 101. So for those of you who are completely new to it, here’s what you need to know about how to read the Bible — for beginners.

The Bible is a single book — but it’s also not. It’s kind of like an anthology, or like a series all bound together.

The Bible consists of 66 smaller books, grouped into 2 major sections, the Old Testament and the New Testament. They can be further subdivided into smaller categories, like law, history, poetry, epistles (letters), etc. All 66 books are inspired by God (2 Timothy 3:16-17), so they all inter-relate. Many have shared “characters,” similar to what you might see with a group of fiction series from a single author who set them in the same town. But they also each can stand alone.

Because each book-within-the-book is self-contained and can stand alone, you don’t necessarily have to just start at page one and read straight through from start to finish. You can, but around Leviticus and Numbers (the third and fourth books) it can get pretty dry and repetitive, and a lot of people burn out, so that might not be the best approach for a total newbie to the Bible.

So where should you start? There isn’t really a right or wrong here. Any place you want to start (and will actually stick with it) is fine; a lot of it is a matter of personal preference. But some books are easier than others, which makes them generally more beginner-friendly.

I think Genesis is an excellent place to start. It’s the beginning for a reason, and it portrays a lot of beginnings: the beginning of the world, the beginning of marriage, the beginning of sin, etc. And most of it is narrative (story), so it’s not too confusing.

Most people suggest starting with the New Testament — either one of the four Gospels (most people recommend John) or one of the epistles (Ephesians and Colossians are both pretty accessible options — also fairly short). I think these are excellent early options, as well, although I still like the idea of starting with Genesis.

So I might recommend reading Genesis, then John, then Ephesians (possibly rolling right into Philippians and Colossians, which follow Ephesians). (Don’t get confused when it comes to John. There’s a Gospel called John, which is what we’re talking about here. John also wrote three epistles, which are called 1 John, 2 John, and 3 John. Right now you want the one that’s just called “John.”) By then you should be getting more comfortable, and can branch out to other books.

I like to use a chart that lists all the chapters of all the books of the Bible, and check them off as I read them. That way I can “jump around” from book to book and still keep track of what I have and haven’t read.

If you’ve been around people who grew up in the church, you might feel like they just know where everything is when they go to look it up! This might be truer than you realize; many Christian kids memorize the names of the books of the Bible in order, the same way kids might memorize the Presidents or state capitals in school. But mostly, this is just a matter of familiarity learned over time. You’ll get there, too!

In the meantime, your Bible should have a table of contents near the front — probably right behind the copyright page. This can help you find a particular book without flipping pages indefinitely.

Within a book, the content is divided first into chapters and then further into verses. When you see a written reference, it will consist of the book name (or abbreviation) and then the number of the chapter and verse separated by a colon (like the hour and minute when you’re writing out a time). So when you see:

Eph. 2:10

That means (the book) Ephesians, chapter 2, verse 10.

If you want more in-depth information about how the Bible is organized, how it was compiled, etc., you might like A Visual Theology Guide to the Bible.

A common mistake in the world of Bible study is to confuse Bible reading with Bible study. There is, of course, some overlap. After all, you have to read the Bible to study it! But if you treat them as synonymous, you can overwhelm yourself during your Bible reading time, and fail to get the most out of both activities.

When I refer to “Bible reading,” I’m thinking primarily of devotional reading — what you would typically do during your “quiet time.” A lot of people assume this should be Bible study. In fact, Adam Deane, although technically differentiating between the two in his book, Learn to Study the Bible, puts a little too much of a burden on the reading, expecting the reader to understand all that he reads. This is asking too much of a simple reading.

One should, of course, read slowly enough to actually take in the words. I’m not suggesting you fly through it without noticing what you read. But parts of the Bible are hard to understand without really digging in, and if you get bogged down in trying to understand the harder parts, you’ll miss out on the benefits of reading.

We read to get familiar with the Bible, which requires moving through it quickly enough to eventually get through it — hopefully multiple times over the years. And we read to take it in as large chunks, in order to better grasp the context of the passages we read or study.

It’s all right if you don’t understand everything you read. As long as you are also engaging in Bible study, you’ll gain understanding there, and the two activities will feed each other — the familiarity and context gained through reading enriching your study, and the study helping you understand more of what you read.

Keep moving. Because the idea of reading is coverage, you’ll want to keep moving through the text. There’s no need to rush — go at whatever pace you need to, look up a word in the dictionary if necessary, etc. — just don’t get bogged down in answering tougher questions.

Take notes. One good way to avoid getting “stuck” is to take notes. Keep paper and a pen or pencil handy, and you can jot down your thoughts as you go. Make a note of anything that jumps out at you from the text.

Also make a note of any questions you have or topics/passages you’d like to study in depth later. That way you can keep moving through the text, but also be sure you can answer the tougher questions through your Bible study at another time.

Use a reading-friendly copy. You can do your Bible reading from any copy of the Bible. But if it feels awkward, consider finding a copy that has features more similar to other books, such as a paragraph format rather than a format with every verse separated. I also like to sometimes read from an inexpensive paperback copy that’s smaller and feels more like a regular reading book in my hands.

Focus yourself. If you find it difficult to read without your mind wandering, try using a simple not-quite-study technique to keep your mind focused.

One thing I’ve done is choose a particular theme for a given read-through, such as “family,” and then watching specifically for that theme to pop up in my reading. (I use an inexpensive paperback copy for this, and highlight that theme throughout the copy with colored pencils.) This provides just enough of a goal to keep me focused, without being so complicated it distracts from the reading.

Another method, suggested in Learn to Study the Bible, is to underline your single favorite verse in each chapter. As you finish up a book, choose which of the underlined verses is your favorite and circle it.

Bible study is a bit different from simple Bible reading. You will need to read the text you’re studying, of course, but the purpose of Bible study is to examine the text more closely to gain a deeper understanding of it.

There are a variety of ways to approach the study of a portion of Scripture, but most use an underlying foundation of what we call “inductive Bible study,” or observation, interpretation, and application.

Observation is simply paying attention to what is in the text: who’s speaking? To whom? Does it mention a location? etc.

Interpretation is considering what the things that are said mean, given their context, genre, etc.

Application is asking why that meaning matters for our lives and putting it into practice.

The single best tip I have for Bible study is to do it. You don’t need to be nervous about “doing it wrong”; just do your best. Like any skill, it can be awkward at first but you get better with practice.

If you have a knowledgeable friend or pastor who will teach or mentor you, don’t be afraid to reach out to them, either.

I previously reviewed Andy Deane’s book, Learn to Study the Bible, and this is an excellent introduction if you need to learn specific skills for studying the Bible. (If you have a friend who’s willing to help you learn, but doesn’t feel confident about teaching you, this can be a great resource to go through together.)

Bible reading and Bible study are different activities, with different, complementary purposes. So at any given point in time, you should have a Bible reading plan and one or more topics for study.

There are a lot of good Bible study resources out there, including a number of “how to study the Bible”-type books. Many of them are pretty good. Learn to Study the Bible, though, by Andy Deane, is the single best Bible study guide I know of for beginners. If you’re trying to learn to study the Bible, or if you’re looking to teach a newer believer to study the Bible, this is the book you want.

The first section of the book is foundations. There’s a little bit of introduction here, but mostly this section describes observation, interpretation, and application, the three key stages of what we call “inductive” Bible study. Each stage is given its own chapter, and is packed full of specifics about what kinds of questions to ask at each stage to get the most out of it, what extra information you might need to know (like how to be sure you’re reading it correctly based on what genre the passage is), and, of course, what each stage is.

The remaining sections in the book, beginning with this second section, are the actual Bible study methods. The forty methods promised on the book’s cover may seem like overkill, but when they’re broken down the way they are, most of them are pretty useful.

Many of the methods in this section are not so much different methods of study, but different methods of organizing your thoughts as you approach a given passage. They’re the type of method you would use as a consistent approach to “everyday” deep reading of Scripture — where you want to do more than just read it, but you might not be wanting to totally plumb the depths, either.

You probably won’t want to adopt all of the methods in this section. Rather, you’ll probably want to choose the one you like best and use it as your default pattern when doing simple Bible study. (Although you may want to try several of them — or even all of them — first to get a feel for them before you settle into one.)

For instance, the “Five P’s” method has you look for a Principle of Conduct, Put Another Way, Personal Struggle, Profit or Loss Anticipated, and Plan of Action for the passage at hand. Of course the book spells this out in greater detail, but this is simply a group of reminders to write out a key verse that tells you how to conduct yourself, rewrite the verse in your own words, make note of how it applies to your life, consider the potential effects of obedience or disobedience, and choose how you’re going to put the principle into action.

A few of the methods in this section differ a little more from the others, and can help you see the passage from a new perspective, without too much extra work.

The third section of the book covers what the author calls “major methods” of Bible study. These, too, are “basic” in their own way. The section addresses studying verse by verse, studying a chapter, a book, a character, a topic or theme, and doing a word study.

These are all important fundamental methods of studying the Bible as a whole, and the book does an excellent job of walking the reader through each one step by step, including specific tips, recommended questions to ask, etc. These methods also provide excellent opportunities to practice using various Bible study tools, such as a Bible dictionary, concordance, topical Bible, or parallel Bible.

This fourth section of the book contains six methods, and they’re a mixed bag. A couple are designed to bring a fresh perspective and “shake things up” if your study is getting a little stale. I wasn’t impressed by these, personally. A few are additional approaches that can be used in tandem with some of the more basic methods to provide a bit more depth or round things out.

The fifth section of the book offers instruction for studying specific portions of the Bible, giving consideration to the elements that make each part of the Bible unique. (For instance, a book of poetry has different considerations than a book of history.) There are sections specifically about studying: the kings, Proverbs, Jesus’ actions & commands, biblical “types,” prayers, miracles, parables, and Psalms.

I was least impressed with this section. Supposedly, these are more accessible methods intended for teens. I think most teens should be able to handle most of the other methods in the book, and most of the methods in this section are a little strange. A few, with adjustments, would be good for introducing elementary school students to Bible study, but with older kids I’d just stick with the basics introduced by previous sections of the book.

I was impressed by the fact that this book is remarkably thorough while still being remarkably accessible. There is a lot of information packed in, and yet there’s absolutely no fluff.

Each Bible study method is a simple, step-by-step walk-through, with whatever additional hints, tips, or information you need to carry out the steps as instructed. These instructions are followed by an example of what the result looks like written out on paper.

Apart from a (very) few of the 40 methods that I found a bit unhelpful, the only caveat I have is that Deane doesn’t draw as strong a distinction as I would like between reading the Scripture and studying the Scripture.

Overall, though, this is an excellent introduction to Bible study and a highly recommended resource for new and/or growing believers.